(NEW YORK) -- As measles continues to spread across the United States, questions have emerged about whether the country will retain its measles elimination status.

The U.S. is currently experiencing the highest number of measles cases reported in more than three decades, in large part due to an outbreak in western Texas that infected more than 700 people and spread to New Mexico and Oklahoma.

Meanwhile, an outbreak in Arizona and Utah currently shows no signs of slowing down and a separate outbreak in South Carolina has sent dozens of students into quarantine.

If spread of the virus continues into late January, it will mean the U.S. has seen a year of continuous transmission, which could lead to a loss of the country's elimination status. Measles would once again be considered endemic or constantly circulating.

The threat of the U.S. losing its elimination status is looming after Canada lost its measles elimination status following a struggle to contain a year-long measles outbreak, public health experts told ABC News.

"I do think that the likelihood that we're going to lose status, especially if things continue the way that they're going, is I think pretty high," Dr. Tony Moody, a professor of pediatrics in the division of infectious diseases at Duke University Medical Center, told ABC News.

State of measles in the U.S.

As of Wednesday, there have been 1,753 confirmed cases across 42 states this year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

There have been 45 outbreaks, so far this year compared to 16 outbreaks all last year, CDC data shows.

Additionally, 92% of cases have been among those who are unvaccinated or whose vaccination status is unknown, according to the CDC.

There have been three measles deaths this year -- the first fatalities due to the disease in a decade -- including among two unvaccinated school-aged children in Texas and one unvaccinated adult in New Mexico.

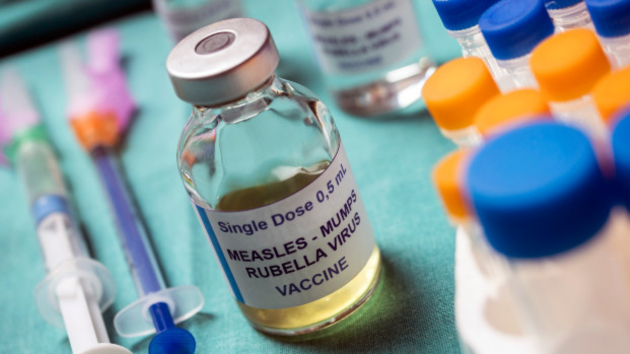

The CDC currently recommends that people receive two doses of the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine, the first at ages 12 to 15 months and the second between 4 and 6 years old. One dose is 93% effective, and two doses are 97% effective against measles, the CDC says.

However, CDC data shows vaccination rates have been lagging in recent years. During the 2024-25 school year, 92.5% of kindergartners received the MMR vaccine. This is lower than the 92.7% seen the previous school year and the 95.2% seen in the 2019-20 school year, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even in states with high MMR vaccine uptake, pockets of unvaccinated or under-vaccinated communities can lead to rapid spread.

For example, in Texas, 94.3% of kindergartners were up to date on their MMR vaccine for the 2023-24 school year, CDC data shows. However, in Gaines County -- the epicenter of this year's outbreak -- 17.6% of kindergartners were exempt from at least one vaccine during the 2023-24 school year, one of the highest exemption rates in the state, according to state health data.

"It's kind of like you have a very dry forest, so any spark that comes in can burn down the entire forest," Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, a professor of medicine and infectious diseases specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, told ABC News. "That's what's happening, which is fewer people being vaccinated, as evidenced by the drop in in people entering kindergarten."

He said one case of measles is like a spark that quickly turns into a blaze as it spread through an unvaccinated community "and that's why it's hard to put out the fire."

How loss of status is determined

The loss of status is determined by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO, an agency of the U.N. that oversees international health in the Americas.

An independent body of experts established by the PAHO -- known as the Measles, Rubella, and Congenital Rubella Syndrome Elimination Regional Monitoring and Re-Verification Commission (RVC) -- meets at least once a year to monitor and re-verify measles and rubella elimination among countries in the Americas.

A person familiar with how PAHO determines loss of elimination status told ABC News that there would have to be compelling evidence that there has been continuous spread of measles in the U.S. since January, when the first cases were reported in Texas and that other outbreaks may trace back to the Texas outbreak.

The person said the committee will get together in mid-2026 to look at the data, write its next report and formally submit it to the PAHO for review. The annual meeting will likely take place in late 2026, unless a previously unplanned meeting is convened beforehand.

"The RVC holds annual meetings with all member states, conducts visits to priority countries, reviews national sustainability reports, and issues recommendations to the Director of PAHO," a spokesperson for PAHO told ABC News. "It may also convene extraordinary meetings with member states to provide recommendations on specific topics or to follow up on outbreak situations. At this time, no extraordinary meeting has been scheduled for next year specifically to assess the U.S. or Mexico situation, but such a meeting could be convened if the epidemiological situation warrants."

Between April 2025 and October 2025, Mexico has seen 4,550 cases, according to the WHO, which could also lead to the loss of its elimination status.

Moody explained that the U.S. having measles elimination status, which it received in 2000, is less of a formal declaration and more of a statement that a county has a relatively low number of cases and no sustained transmission.

Loss of status would similarly be a statement that a country has sustained transmission and that the virus is constantly present, he said.

"What does it mean from a public health perspective, or a parent's perspective, it means that we have a higher risk for seeing transmission, and that if someone goes to a place where there is sustained transmission, there's kind of an increased risk and, truthfully, you can pick it up just about anywhere," Moody said.

Canada's loss of elimination status

Earlier this month, the Public Health Agency of Canada said it was informed of the elimination status loss by PAHO after more than 12 months of continuous measles transmission. Canada's outbreak began in late October 2024, and the county has seen more than 5,200 confirmed and probable cases since then, data from the health agency shows.

As a result, the Americas region lost elimination status as well.

Canada can re-establish its measles elimination status if measles transmission related to the current outbreak is "interrupted" for at least 12 months, according to the county's health officials.

"Given that we share one of the longest borders in the world with Canada. It's not as if there's some magic barrier between U.S. and Canada," Moody said. "If there's transmission in Canada, we're going to get it in the United States. ... I'm not saying that Canada has put us at risk. We've kind of put ourselves at risk but ... I do see it as being a highly likely thing that we're going to see continued transmission."

Canada will present and implement an action plan under PAHO's regional framework to increase immunization coverage, reinforce surveillance systems and ensure rapid outbreak response to stop spread. This shows what the U.S. would likely experience if it lost its status.

"If we lose our status, it'll be hard to regain it," Chin-Hong said, noting how many workers have been laid off at HHS that might have helped control large outbreaks. "Not only loss of expertise, but just loss of the workforce in general, the people who go out and do the surveillance and contain the epidemic by vaccination efforts and all that. ... It just denotes how fragile public health gains are. In general, it's easy to lose it and hard to get it back."

How to prevent further spread

Public health experts told ABC News there are several steps that can be taken to help control the spread of measles in the U.S. including increasing funding to public health for monitoring and surveillance as well as spreading awareness about how dangerous measles can be.

However, they add that the best way to stop the spread is through vaccination, both to protect yourself and the most vulnerable individuals.

"We can't control the people who are unable to get vaccines because they're being treated for cancer, because they are born with an immunodeficiency," Dr. Aaron Milstone, pediatric director of infection prevention at Johns Hopkins Health System, told ABC News. "What we can control is everyone else in the community who is eligible for a vaccine, who does not take it, and that's the reason that measles is spreading, in part, because the herd protection from our community has gone down."

As an extra step, public health agencies have previously recommended early MMR vaccination for infants living in outbreak areas or traveling internationally.

This would result in three doses overall: an early dose between age 6 months and 11 months and then the two regularly scheduled doses at age 1 and between ages 4 and 6.

Milstone said the recommendation to give a child their first MMR dose at age one was under the assumption that they likely would not be exposed to measles before then and that antibodies passed in utero would help protect them during their first year of life.

Now, with the continuous spread being seen, "are we going to have to rethink our recommendations for when to vaccinate kids in the U.S.?" Milstone said.